Twilio: Racing Up the Stack?

Erstwhile Columbia professor Bruce Greenwald, in his book Competition Demystified, wrote that over time even products and services that initially might require a high level of sophistication to build eventually commoditize and become easy to copy.

The example he gives is toaster ovens:

Almost everybody makes toasters.

[…]

There are more than fifty brands of toasters available in the United States. […] Since most of the toasters come from companies with extensive small appliance lines, and a few from diversified giants like Philips and GE, the financial statements do not reveal how profitable toasters are to their manufacturers.

But with no barriers to entry here, it is unreasonable to assume that any manufacturer is earning an exceptional return on its toaster assets. Though they differ from one another in functional and design features, one toaster is pretty much like another.

In a chapter tracing the evolution of Cisco Systems—the networking gear manufacturer—during the late 90s, Greenwald notes that even Cisco’s complex products eventually turn into toaster ovens:

How different is a complicated and expensive piece of network equipment—a router, smart hub, or LAN switch—from a toaster? Initially very different, but ultimately, not so different at all. The success of Cisco in its original business attracted new entrants, most of whom could not put a dent in Cisco's performance during the first fifteen years of operations.

He concludes:

What matters in a market are defensible competitive advantages. […] Toasters are highly differentiated, but there are no barriers to entry and no competitive advantages in the toaster market. When products come to take on these characteristics of toasters, as most of them do over time, exceptional returns disappear.

Greenwald’s point is true in a very general way: companies must constantly escape the gravitational pull of commoditization. Successful companies will always have copycats; it’s a business imperative to continue to differentiate one’s products and retain competitive advantage.

This is a hard thing to do! When the iPhone was introduced in 2007 it was “obvious” that it too would eventually be commoditized. Why wouldn’t it? This scenario is likelier than the alternative.

This became even more “obvious” when Android was released the following year: a free operating system allows anyone to compete making better hardware. It’s hard to beat free.

And yet that’s not what happened. Against the odds, Apple has succeeded in building a developer community, as well as a software ecosystem around its iPhone, all the while creating differentiation through design, features, and customer appeal. The result: Apple is the world’s most valuable company (Saudi Aramco is unlikely to keep the crown for long).

This brings us to Twilio, which built an early lead in voice and SMS programmability by creating a developer-friendly API.

It was the first company to create an excellent developer experience to solve a very hard problem: allow Twilio’s developers to make phones ring and text messages move around without having to touch any underlying infrastructure or spend millions of dollars buying telco equipment.

But over time, Twilio’s success attracted competition: Bandwidth and Sinch are publicly traded companies that provide similar functionality, as do private companies like MessageBird and Plivo.

Despite Twilio’s initial advantage—its Super Network abstracts away the complexity of connecting developers with telco infrastructure around the world, with routing for best pricing—the competition is now “good enough” and many customers feel the services are fungible.

In other words, for a certain type of workload, Twilio’s initial products have turned into toaster ovens.

This reality is not lost on Twilio’s founder and CEO Jeff Lawson. In fact, in Build vs. Die, the first chapter of his book Ask Your Developer, Lawson quotes Darwin: “It is not the strongest species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the ones most responsive to change.”

Twilio’s IPO was in 2016 and a mere two years later, Lawson was responding to change, employing a “laddering strategy”: he began using the gross profits produced by Twilio’s initial products, plus the currency afforded by having publicly traded stock, to begin moving up the stack into SaaS products with higher gross margins.

His first acquisition was SendGrid, a company very much in Twilio’s mold—a developer-facing company with APIs for sending email—except it has SaaS margins of over 75 percent.

At the time of the SendGrid acquisition—late 2018—Twilio was able to conclude the deal with a mix of cash and stock which resulted in a multiple of around 13x SendGrid’s trailing twelve month revenues. For a business growing 34 percent, this was a great deal. (As a point of comparison, this multiple is the same that Thoma Bravo recently paid for SailPoint and AnaPlan, on forward revenue estimates, after the dramatic market decline in early 2022. Thoma Bravo is doing this because they believe, I presume, that these deals will make them a lot of money.)

Since then, Twilio has made another smart acquisition: Segment, a CDP (customer data platform) with 75 percent gross margins growing over 50 percent, at a revenue multiple of 17x (richer, but not nearly as high as, say, Salesforce’s acquisition of Slack at over 30x sales which made sense despite appearing excessive).

CDPs, though, are platforms that must be integrated with adjacent products to be valuable. Most companies that have a CDP also have advertising, marketing, or other customer engagement solutions.

Adobe, which owns commerce and advertising analytics properties, has its own CDP; so does Salesforce, which has CRM and commerce, among other properties. Amplitude, which embeds analytics inside mobile apps, just created one. And George Hu, who joined Twilio from Salesforce to lead its go-to-market efforts, recently left Twilio to join mParticle, another CDP (presumably, mParticle will eventually sell itself).

Adobe and Salesforce have the assets to connect their CDP to marketing analytics and outcomes. Twilio must integrate Segment into SendGrid, messaging and its other APIs (such as Flex, Twilio’s call center product), or Segment won’t be of much value.

Other recent acquisitions, however, are less straightforward. Last year, Twilio spent $850 million to acquire competitor Zipwhip. At the time, CFO Khozema Shiphandler was asked about the rationale for the deal. This was his reply:

And then I think Zipwhip for us was an opportunity to—again, financially compelling, a good business, good team, and it's—it also fits into our kind of broader supply chain strategy. So, as you're aware, knowing the business —or the totality of our business quite well, like toll-free is one of the channels within messaging that customers avail themselves of. Long codes, short codes, toll-free, what have you. And it's a very valuable one, and there's a great technology that sort of underpins that with Zipwhip. And to us, it felt like a good asset to be under our ownership. We happen to know the company really, really well because we've worked with them for 5 to 10 years, and they have a great team. So that worked out pretty well, too, and they've got some really interesting software inside the company as well.

Yet Twilio refused to disclose Zipwhip’s growth rate and profitability. Looking at what Twilio has disclosed, it appears Zipwhip does about $120 million per year in revenue and is not profitable.

Then there was the $750 million Syniverse investment, made in May 2022, in exchange for a minority stake. Syniverse is a critical piece of Twilio’s supply chain. If a Verizon customer wants to send a text message to an AT&T subscriber, it can’t happen without the message first going through Syniverse or another company like it.

But here again Twilio has failed to articulate the value proposition of the Syniverse investment; $750 million is a lot of money. Besides some boilerplate language on “driving long-term growth,” Twilio revealed nothing.

Lack of Transparency

Twilio suffers from the same problem that has hurt the valuation of companies like Spotify: lack of transparency. Investors don’t have good visibility into the effectiveness of Twilio’s capital allocation. They also don’t have visibility into Twilio’s gross margins.

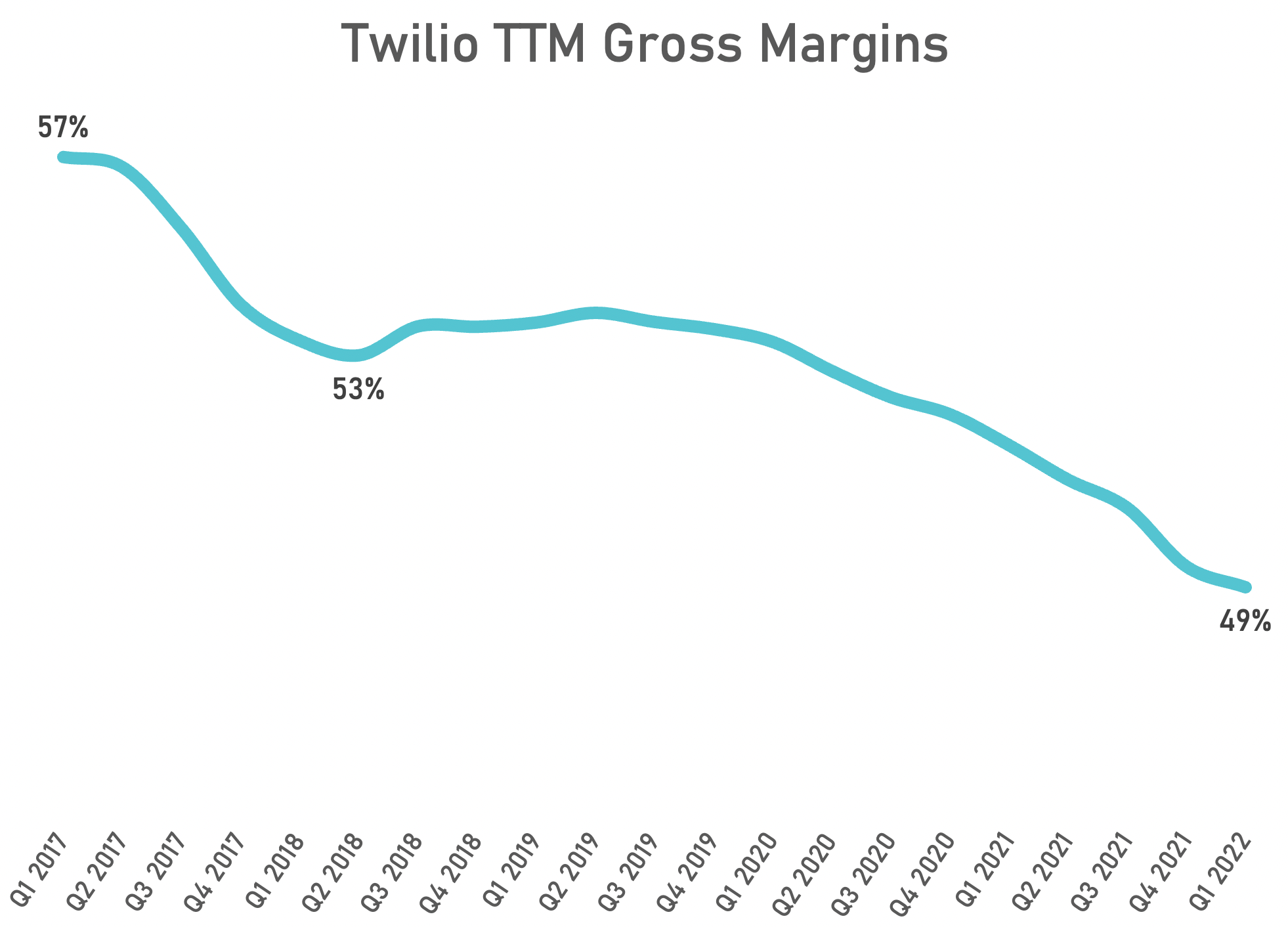

Twilio’s gross margins have declined consistently over the last five years. In a vacuum, higher or lower gross margins aren’t good or bad; what really matters is why gross margins are trending in a certain direction.

The decline in Twilio’s gross margins stems from its fast-growing messaging business and the competitive pressures therein. International business is more competitive and growing faster, dragging down gross margins.

Sinch, based in Sweden, has gross margins in the mid-20s. Only about 37 percent of its revenues are from the US. Bandwidth, with nearly 90 percent of its revenues in the US, has gross margins of around 44 percent. Twilio’s revenues skew 65 percent US and 35 percent international.

This decline reveals two facts. The first is that competition is intensifying for Twilio’s core business, not only from the likes of Sinch and Bandwidth, but also from what’s on the horizon.

In early June, Apple introduced Passkeys, a standards-based technology aimed at replacing passwords. From TechCrunch:

Apple demonstrated “passkeys” at WWDC 2022, a new biometric sign-in standard that could finally kill off the password for good.

It’s no secret that passwords are insecure, with easily guessable credentials accounting for more than 80% of all data breaches, per Verizon’s annual data breach report. Passkeys eliminate the need for passwords entirely, according to Apple, and are much less susceptible to being stolen in the case of a data breach or phishing attempt.

According to Apple, Passkey uses public key cryptography. The public key, which is not a secret, is shared freely. The private key is stored in Apple’s secure iCloud and only accessible through a user’s trusted device through biometric authentication. This way, it becomes much harder for a user’s private key to be compromised, and phishing attempts are impossible.

For Twilio, the elimination of SMS-based authentication would be yet another headwind: it would have fewer two-factor authentication emails flowing through its pipes.

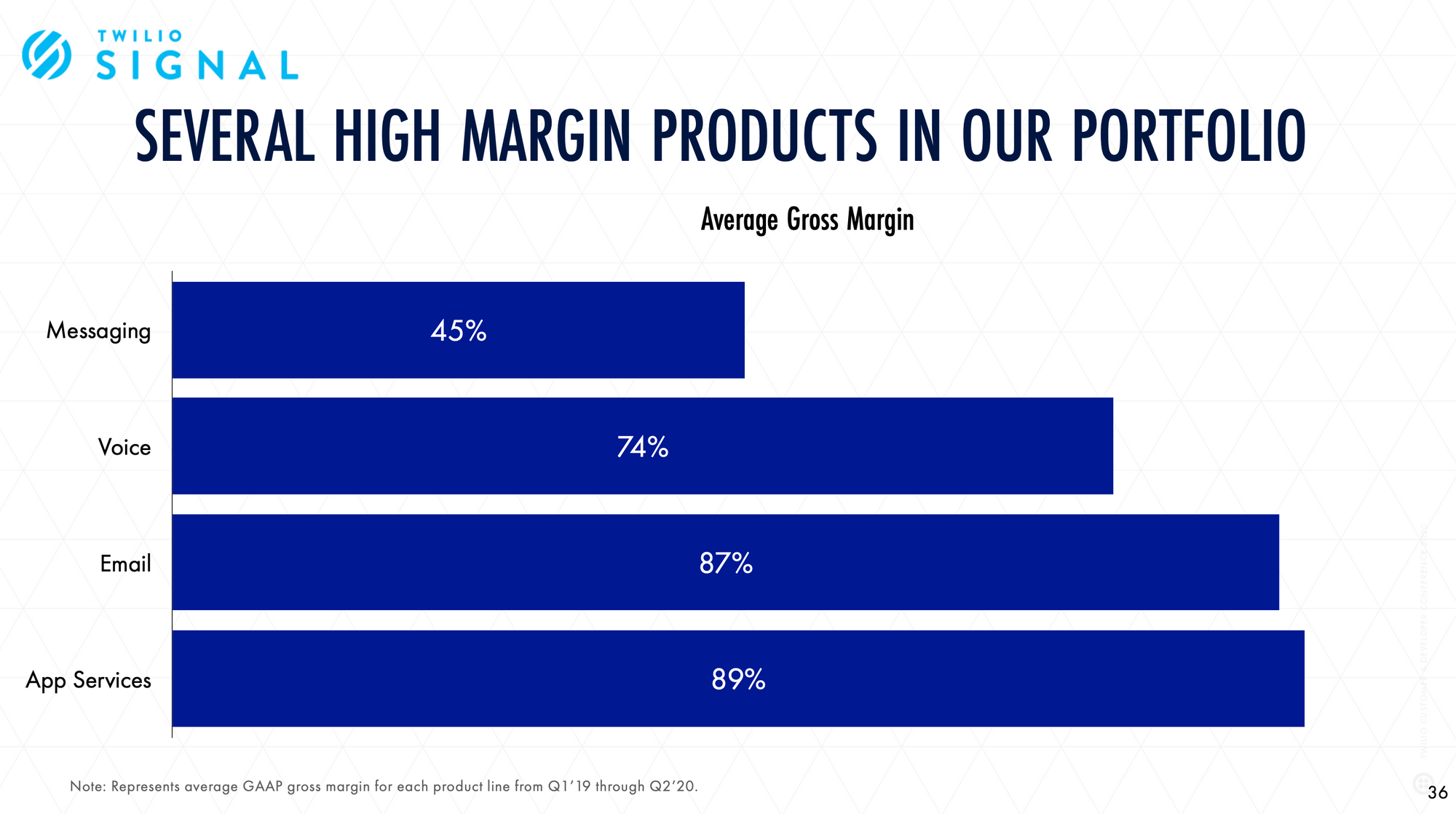

The second fact revealed by Twilio’s declining gross margins is that its higher gross margin products—SendGrid, Segment, Flex and others—aren’t yet big enough to move the needle.

Twilio has, however, shown investors some clues. In its last investor day, held in 2020, the company explained that these other products do indeed have higher gross margins, as expected:

Acquired properties are doing well: SendGrid’s revenues its accelerated from 31 percent growth in 2018 to 36 percent in the first half of 2020.

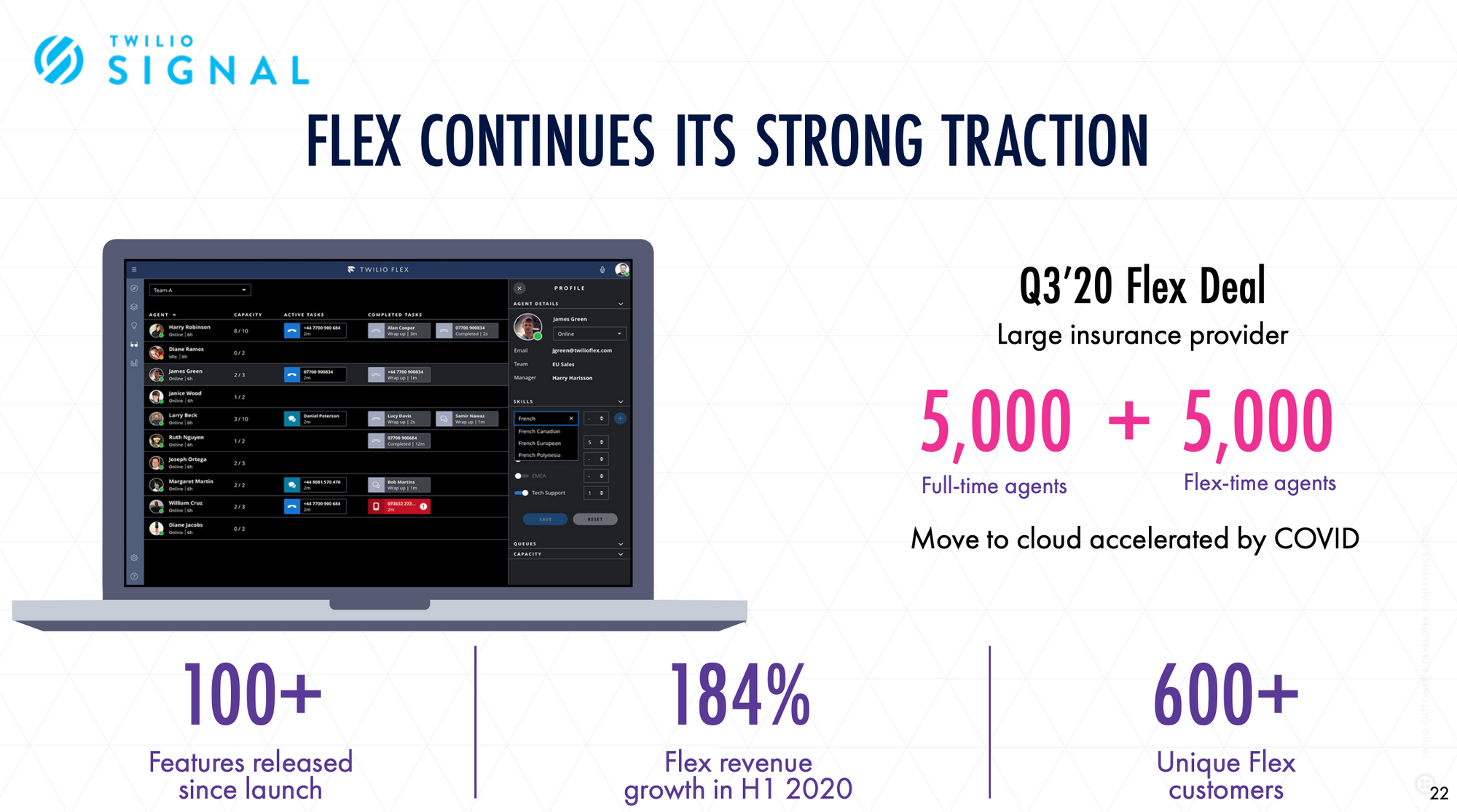

Organic innovation also has the potential to lift gross margins. Noticing that its customers were using Twilio’s APIs to build call center-like functionality, Twilio launched Flex, its higher-level API to build fully programmable call centers. Flex carries gross margins much higher than the corporate average and grew 184 percent in the first half of 2020:

Flex continues to do well. In September 2021, Jeff Lawson noted:

We're really happy with how Flex is going. I know we don't break it out separately, but if you looked at Flex independently, I think you'd look at its momentum and say it's one of the fastest-growing SaaS products on the market.

Yet it’s impossible to verify this because investors can’t see the numbers. One-off investor day disclosures don’t seem to work; investors like to see the evolution of the business every quarter. Increased transparency tends to help, not hurt companies. In the post on Spotify, I noted:

Companies that have broken out their segments often see their stock price increase. When Amazon broke out its AWS segment, for instance, the stock reacted positively. Investors were surprised to see how profitable and fast-growing it was. The same thing happened when Alphabet broke out its “Other Bets.” Investor saw how much money Other Bets were losing, and how profitable the core business looked in comparison.

Meta’s (née Facebook) stock did the opposite when it broke out the $10 billion losses in its incipient AR/VR segment, Reality Labs. But I contend that wasn’t because of these losses—which were widely expected—but rather because of the $10 billion revenue headwind as a result of Apple’s ATT.

But breaking out Reality Labs probably instilled additional discipline on Meta’s expense management, particularly since Mark Zuckerberg promised in the company’s earnings call to continue funding it, but only if it allows Meta to grow its overall profitability.

Spotify should follow suit: give investors a breakdown of gross margins beyond just “Premium” and “Ad-Supported,” which currently includes all podcast investments. Instead, clearly itemize revenue and cost of revenue for Music, Marketplace, Podcasts, and all future verticals.

This additional disclosure will serve as a forcing function for Spotify to deliver. Analysts and investors can judge whether the company is moving in the right direction. It also better aligns investors and Spotify employees, since everyone will have access to the same metrics.

Segmenting the business and showing gross margin progress will likely result in a lift to Spotify’s share price, or at least will allow investors to value the pieces better. It’s a win for employees and a win for shareholders.

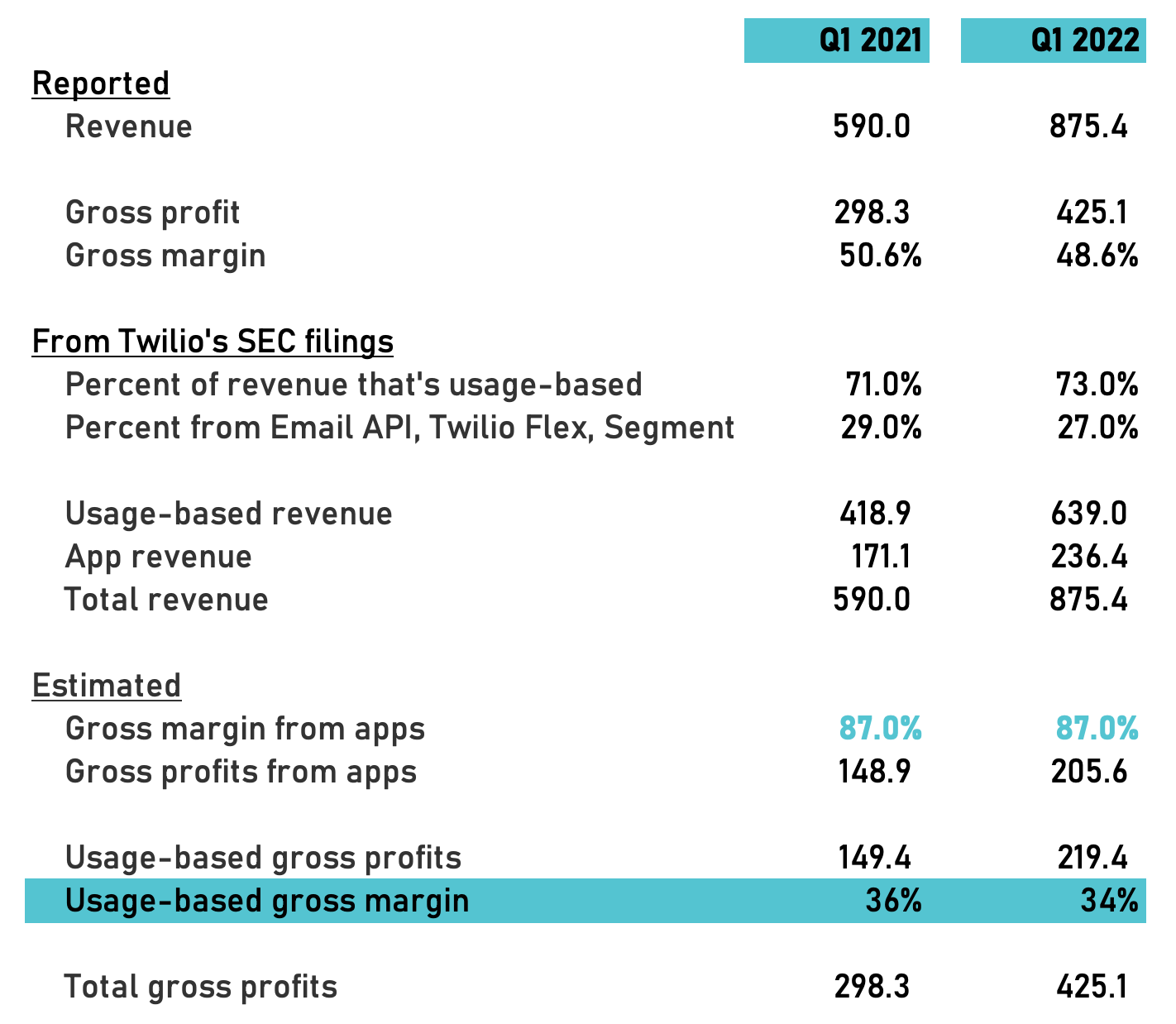

At the very least, Twilio should report its revenue in two line items: usage-based, and app revenue. This breakdown is an easy ask: Twilio already reports the percentage for each in its SEC filings, but leaves the breakdowns as an exercise for the reader.

Let’s take a stab at it:

Assuming Twilio’s family of apps carry gross margins in the neighborhood of 87 percent, this exercise implies that Twilio’s usage-based revenues had a 34 percent gross margin in the most recent quarter.

Explicitly breaking this out for investors would allow the company to demonstrate, measure and track its progress in evolving the business into a higher margin business over time.

Who Needs Higher Gross Margins?

Twilio’s gross margins don’t have to go up. But there are two reasons why they should, and they both have to do with Twilio’s stock price.

Twilio trades at around 3x revenue, an incredible discount from where it traded just a few months ago, but double the multiple of Bandwidth or Sinch (although Twilio is growing much faster).

If Twilio’s gross margins keep declining, its valuation might continue on the same trajectory.

The second reason is expectations. Twilio has repeatedly told investors to expect gross margins to march up to 60-65 percent. This would allow the company to reach its target of 20 percent non-GAAP (before stock-based compensation) operating margins.

Implications for Investors

If we assume that Twilio can deliver its goal of 30 percent revenue growth through 2024, and then grows 25 percent after that, it’ll do about $8 billion of revenue in 2025.

Diluting the company’s share count by 3 percent a year, and assuming the company can deliver on its 20 percent operating margin target, Twilio should put out about $5.5 in earnings per share.

At 25x earnings, the stock would be worth $137, up 48 percent from the current stock price of $93. This would be about 17 percent compounded annually. If Twilio can maintain a higher growth rate and trade instead at 30x earnings, the upside would be 78 percent or 26 percent compounded annually.

The big question is: can Twilio race up the stack fast enough to deliver these earnings by then, or will investors have to be more patient?