Shopify: A Rake Not Far Enough

Bill Gurley, a venture capitalist, once wrote a post called A Rake Too Far: Optimal Platform Pricing Strategy.

“Rake” is the term for what percentage of a transaction is kept by a platform. For instance, the online travel company Booking.com charges hotels 10 percent of their revenue as a listing fee; eBay charges about 10 percent of the listing amount, Amazon gets 12 percent from its merchants, and Apple charges 30 percent on App Store purchases.

All these amounts are dated, since the post was written in 2013 (except for Apple’s 30 percent, which remains the same). But the point remains that successful platforms charge a variety of take rates and Gurley explained that there might be a strategic advantage in charging a low take rate, since it creates a win-win situation between platform provider and supplier.

He gives the example of Booking which, after undercutting Expedia by two thirds, was able to expand rapidly in Europe. He also cites the example of oDesk, the precursor to publicly traded company Upwork, which cut its take rate from 30 percent to 10 percent, also allowing it to surpass its nearest competitor.

Gurley cites these examples of 10 percent take rates as amounts that are high enough to sustain a platform but low enough to inflict pain on any would-be competitors.

What happens, though, when the take rate is too low?

Shopify’s Low Rake

Shopify is an online platform for ecommerce. Anyone can sign up and start selling in minutes. Shopify makes money in two ways. First, it charges a monthly subscription fee for use of its software (the starting price is $29 per month). Second, it gets a cut of sales made through a merchant’s online store by either acting as the payment processor (in partnership with Stripe), or if the merchant opts not to use Shopify as the payment provider, by taking a small payment fee anyway.

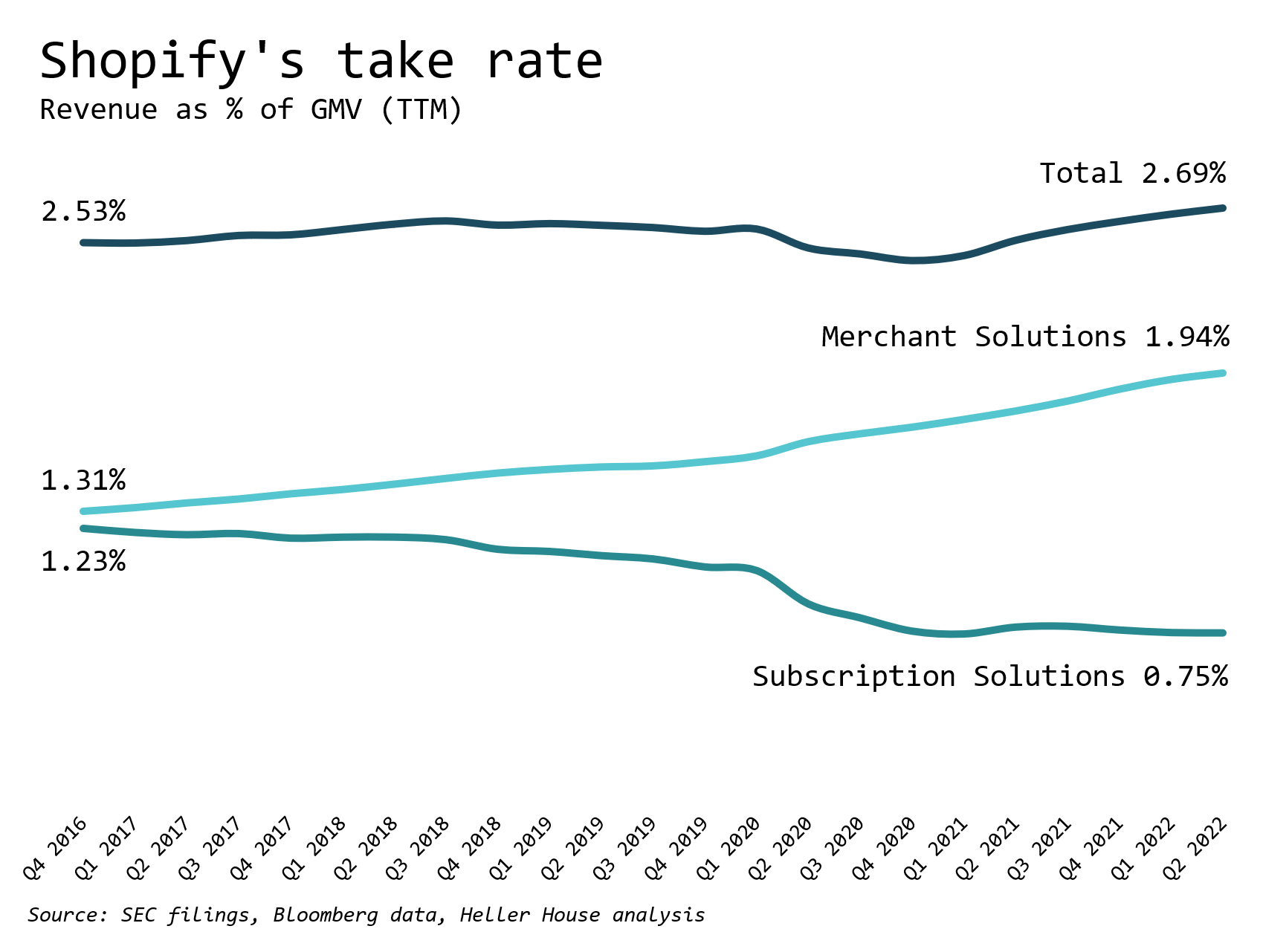

Shopify’s take rate is not close to Apple’s 30 percent; it’s not close to Amazon’s or Booking’s or anyone else’s take rate. Instead, for the last twelve months ended in Q2 2022, Shopify’s take rate was a tiny 2.7 percent, up just a bit from where it was five years ago:

That total of nearly 2.7 percent can be decomposed into what Shopify calls its “Merchant Solutions” (mostly payments, loans, and soon, fulfillment) and “Subscription Solutions” (mostly the software subscription).

This 2.7 percent is peanuts. It’s as if Shopify’s management team read Gurley’s memo from 2013 and said, “Tell you what, we’re not cutting the take rate from 30 percent to 10 percent, we’re going to cut it from 10 percent to less than 3 percent! Nobody will be able to compete with us!”

And there may be an element of truth to this. Shopify has been very successful since its IPO, growing its number of merchants from around 250,000 to over 2 million and scaling the GMV—gross merchandise volume, or the amount of stuff sold by its merchants, measured in dollars—from under 8 billion to 186 billion.

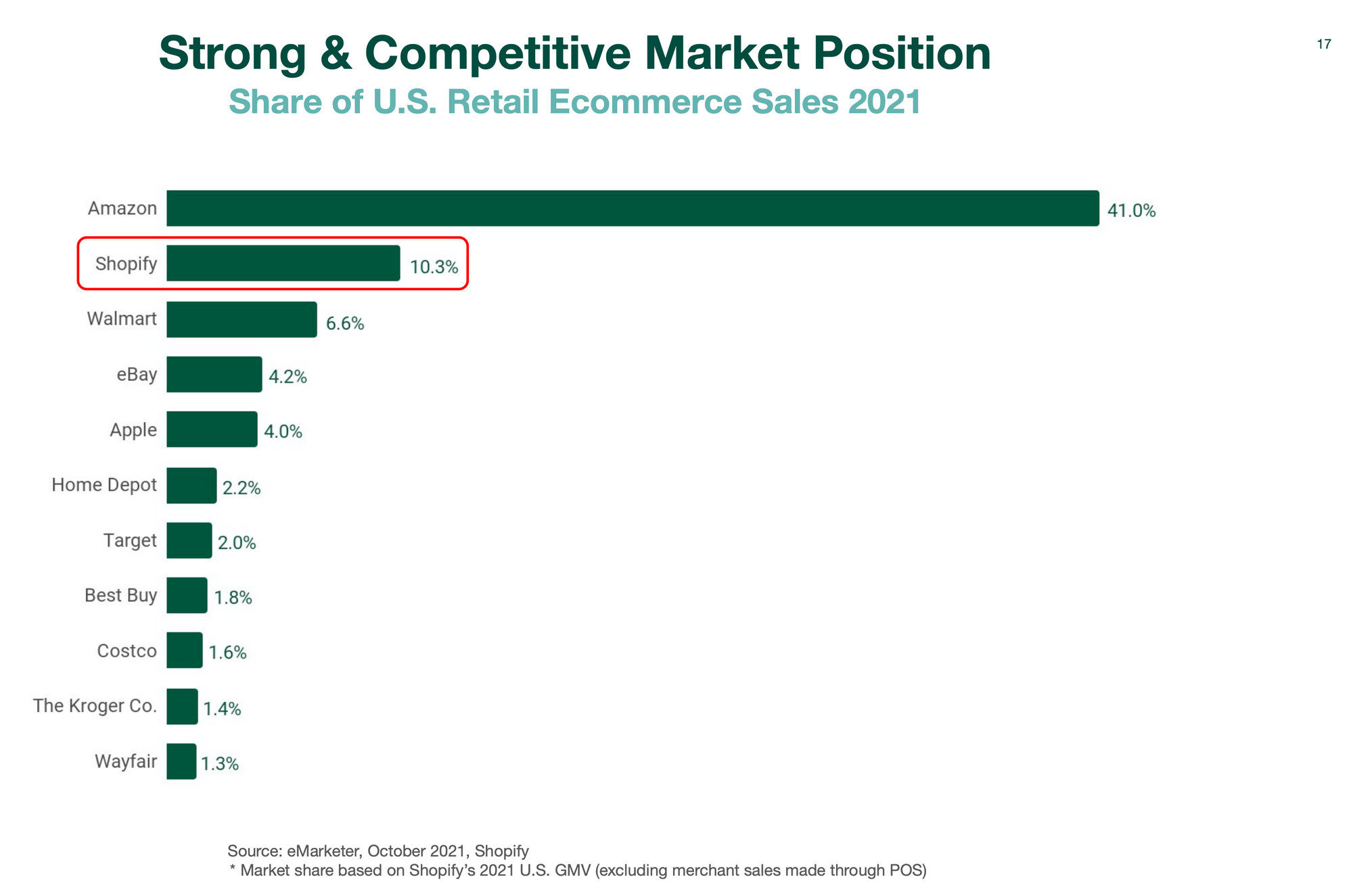

In fact, the merchants using Shopify’s platform are selling so much stuff, Shopify likes to point out that measured in aggregate, the company is a bigger retailer in ecommerce than eBay and Walmart and second only to Amazon:

Shopify’s positioning as the lowest-take-rate ecommerce provider should give it a “strong & competitive market position” as indicated by the title of the slide.

For many years, this has been the bull case on Shopify: that it would be able to grow faster than its competitors like BigCommerce and Demandware, lock up the “entrepreneurship” market for up-and-comers as well as the market for larger enterprise customers, and eventually, increase its take rate.

In fact, when running a discounted cash flow model on Shopify, the only way the stock price ever made sense was if the take rate increased. And why wouldn’t it? Shopify would be able to layer on more products and services—like advertising, marketing, fulfillment, accounting, bookkeeping, customer service and the like—and merchants would be happy to pay Shopify more over time.

Yet despite what Shopify calls its “continued innovation” in releasing new features, it hasn’t been able to raise its take rate at a commensurate level.

Huge Ambitions Require Huge Investment

This matters, because Shopify is famously ambitious. Its founder and CEO, Tobi Lutke, once Tweeted that he would like to one day buy Amazon. He frequently talks about building a “100-year company.”

Venture capitalist John Doerr likes to talk about the difference between “mercenaries and missionaries” and has pointed out that real entrepreneurs are missionaries. They create mission-driven businesses, and the irony is that in the end, the missionaries end up making more money than the mercenaries. Shopify positions itself as the ultimate mission-driven company.

Yet none of this is going to work unless Shopify makes money. I’m not referring to profits or free cash flows; it’s OK to reinvest aggressively while building out the company. Rather, I’m referring to revenues and gross profits, the fuel for all that is required if Shopify is to fulfill its mission.

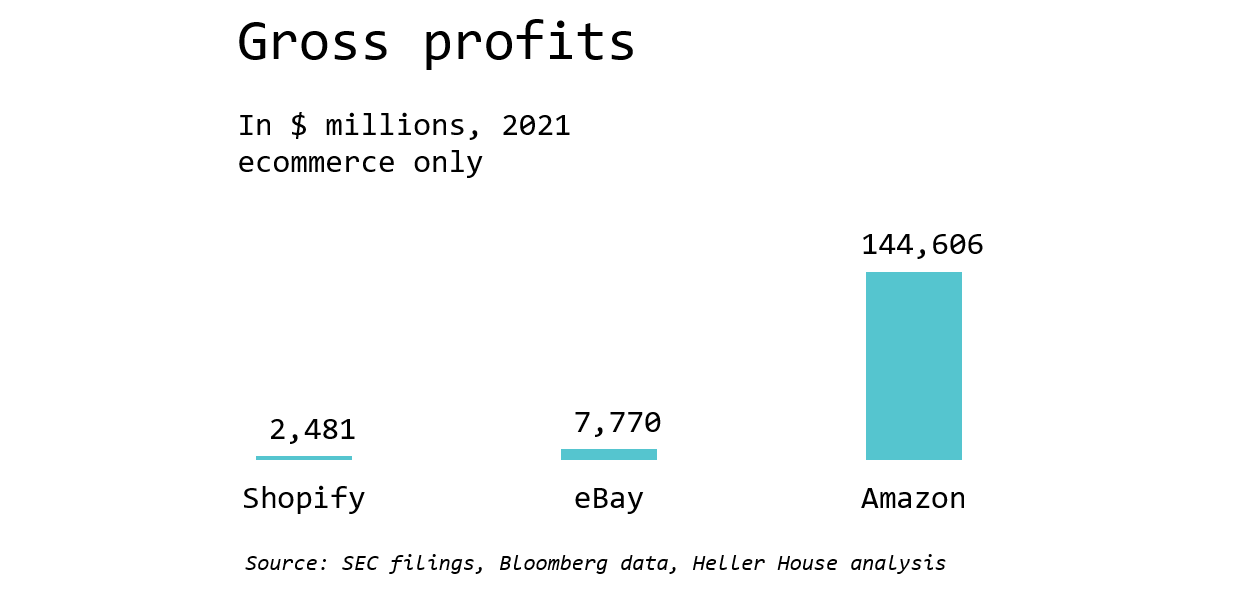

Despite Shopify having a 10.3 percent slice of ecommerce, as it indicates in the slide above, the gross profits it earns from that slice are tiny. Here’s a comparison of Shopify’s gross profits relative to Amazon and eBay:

Even though eBay’s market share is 60 percent smaller than Shopify’s, its gross profits are 3x greater. To estimate Amazon’s ecommerce gross profits, I took reported gross profits and assumed AWS has 85 percent gross margins and deducted that from the total to arrive at an estimated $144.6 billion in ecommerce gross profits. It’s a whopping 58x more than Shopify earns even though its market share is only 4x larger.

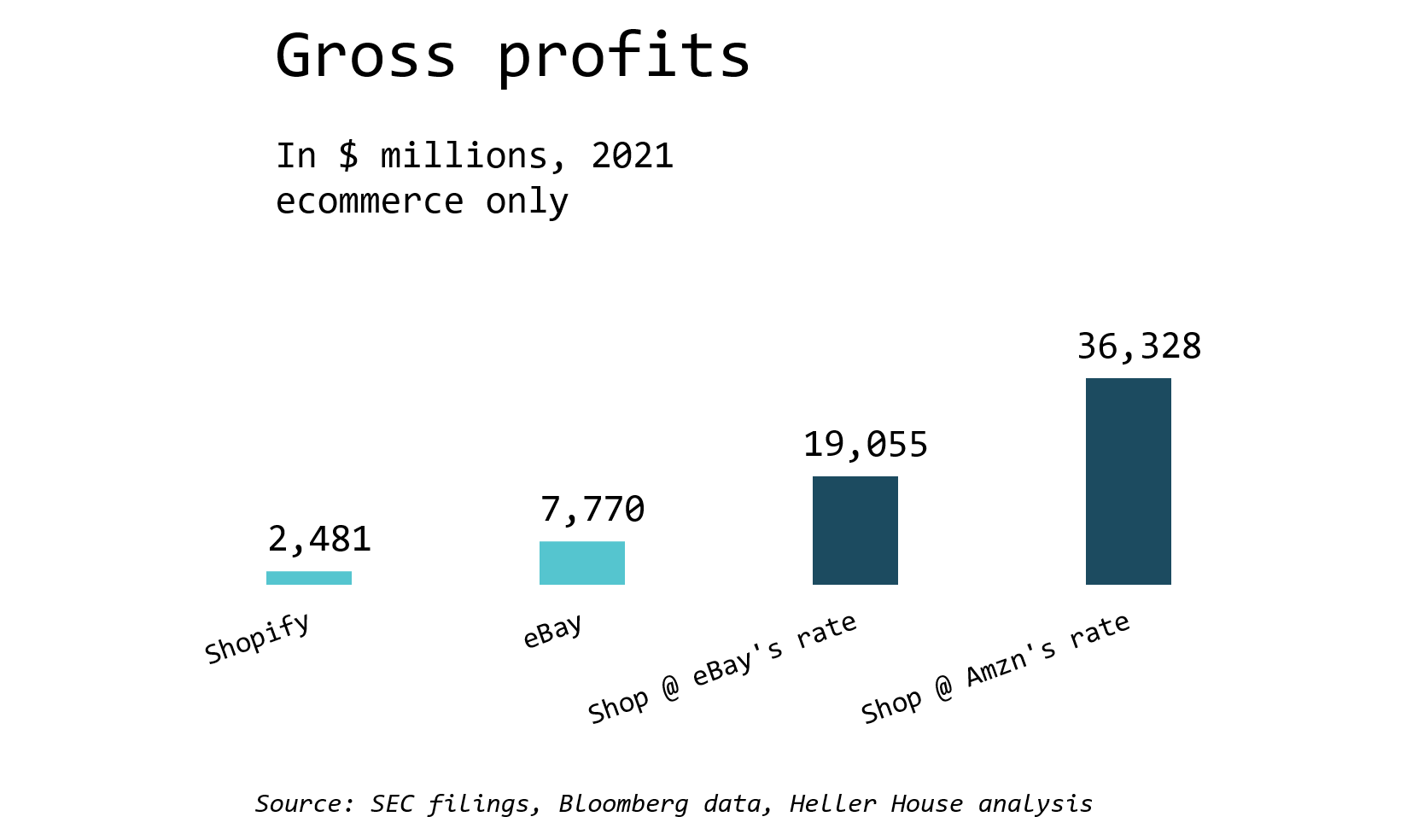

If Shopify could earn a share of ecommerce gross profits equivalent to its market share, its gross profits would be between 8x and 15x greater, depending on whether it could monetize as well as eBay or Amazon:

The obvious retort is that both eBay and Amazon are marketplaces: they bring a huge supply of customers to their merchants. Rather than spending money on Facebook ads, merchants on these two platforms can just show up. All the customer acquisition is built into their rake.

This is an additional problem for Shopify. While the company claims that it has not seen an effect from Apple’s IDFA on its merchants, this is very hard to believe. Meta (Facebook) is seeing an enormous headwind this year. It’s more likely that Shopify’s growth slowdown is in part due to IDFA but it has been unable to disentangle this from other macro factors.

Now that ads on Facebook are less effective, Shopify’s native integrations with Facebook, allowing customers to close the loop without transferring data (and thus avoiding Apple’s restrictions) become even more valuable. Yet so far investors cannot discern this in Shopify’s financials.

This gap in monetization from not having a marketplace is one reason why Shopify’s shareholders have for years been asking if Shopify is going to create some type of discovery into its Shop app. So far, Shopify doesn’t seem interested.

A Sign of Weakness?

But what if Shopify’s low take rate isn’t a sign of strength, but rather, a sign of weakness, a sign that the company can’t raise prices for its software, or that merchants aren’t willing to pay much for the privilege of being on Shopify’s platform?

One of Shopify’s competitive advantages has been its partner and developer network. Earnings releases frequently tout the number of partners who referred merchants to Shopify, and developers build functionality that augments the core Shopify store.

Thus, the $29 dollars that a merchant pays Shopify on the starter subscription plan is just that: the start. In addition, it will end up paying a long list of developers their own monthly subscription fees for various apps to augment the core Shopify functionality.

Some have called this Shopify’s “immune system” since these developers will augment Shopify and keep it competitively advantaged. By not internalizing these features and allowing developers to make a living, Shopify thus ensures its own survival. It allows Shopify to fulfill Bill Gate’s definition of a platform: “A platform is when the economic value of everybody that uses it exceeds the value of the company that creates it.”

Yet here’s one entrepreneur who thinks too much money goes to apps, and too little to Shopify:

This screenshot shows both why @Shopify can still win, and why it is losing right now.

— Moiz Ali (@moizali) July 28, 2022

Far too much to apps. The Shopify backbone is weak, and has to be supported with dozens of apps to make your store work.

Far too little to Shopify. pic.twitter.com/DjeWVJLyDH

The replies to Ali’s Tweet are interesting. Most people are in the “this is a feature, not a bug” camp, but I suspect most people don’t realize how little money Shopify makes.

While it talks about “arming the rebels” against Amazon, Amazon uses its hefty take rate to build features that threaten to crush Shopify. Ali makes a similar point in another Tweet thread. What good is being missionary if you can’t make enough money to accomplish your mission?

Buy With Prime

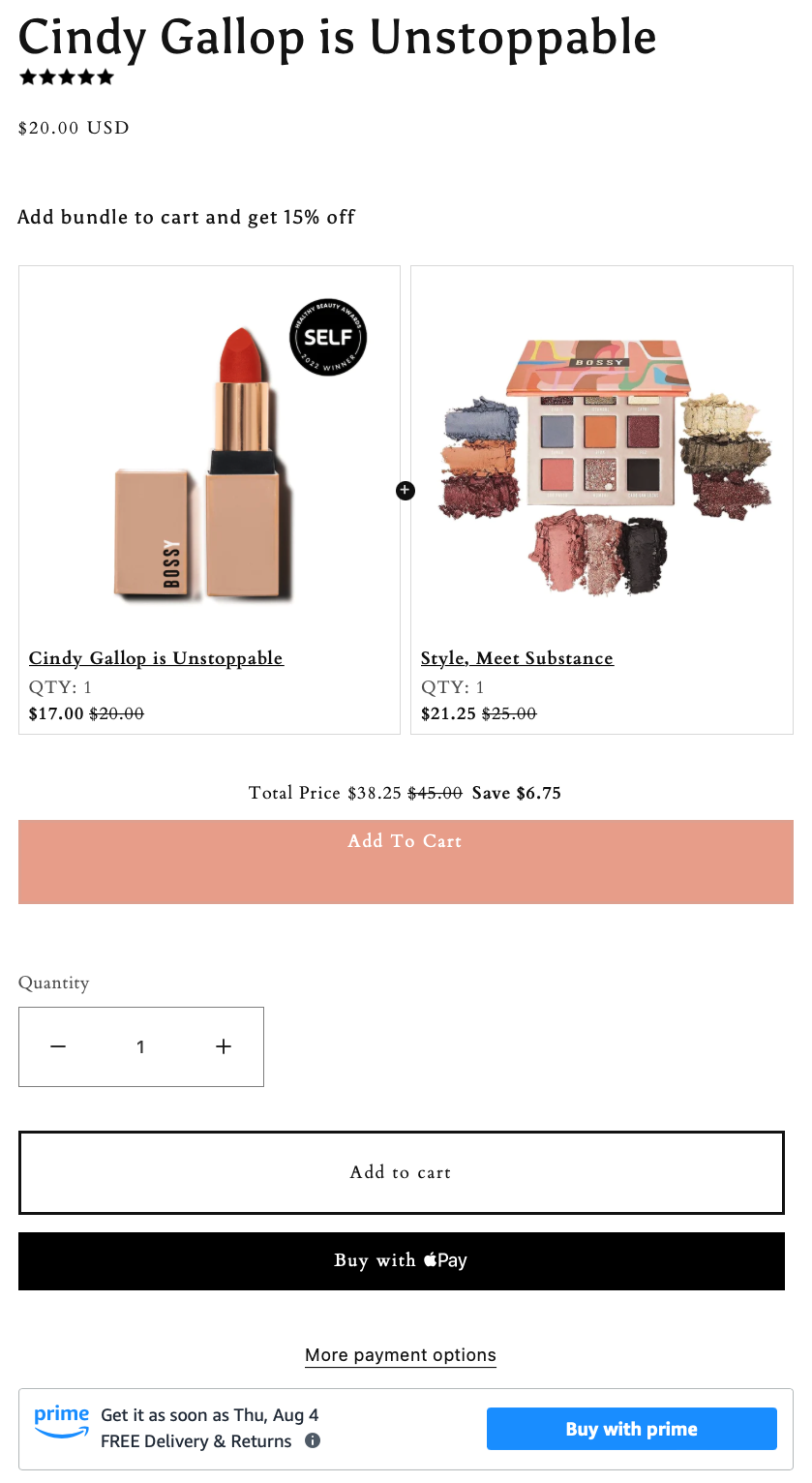

A few months ago Amazon introduced “Buy with Prime,” a new offering that allows any existing Shopify merchant that already has FBA (Fulfillment by Amazon) to add a button to their store that says “Buy With Prime.”

It’s a game-changer. Customers are much more likely to convert—that is, hit that buy button—when they have certainty on the delivery date. Here’s an example of Buy with Prime in the wild:

Shopify recently invested over $2 billion in the acquisition of Deliverr, which it claims will eventually allow all its merchants to effectively compete with Amazon’s logistics.

There are a few problems with this.

First, the deal with Deliverr just closed, and only a tiny percentage of Shopify’s merchants can take advantage of Deliverr’s logistics right now (Shopify’s CFO referred to Deliverr’s coverage as “a subset of a subset” in the last earnings call).

Second, it’s hard to believe that Shopify will in fact be able to close the gap in an “asset light” way, as it claims, while Amazon has sunk tens of billions, if not hundreds of billions, into its logistics infrastructure.

Third, while Buy with Prime is not yet widely available, any take-up of the feature from existing Shopify merchants cuts two sources of monetization from Shopify. This is because Buy with Prime bundles both payments and fulfillment.

Buy with Prime is therefore a threat aimed right at the heart of how Shopify monetizes. Rather than earning money through payment flows, Shopify would be left with a smaller payment fee and most of the payment “rake” would accrue to Amazon.

And then, the entire fulfillment rake would accrue to Amazon, not Shopify. This would make it even harder for Shopify to earn a return on its over $2 billion investment in Deliverr, not to mention the additional capital it’ll have to invest in fulfillment in the coming years.

Impact on Shopify’s Financials

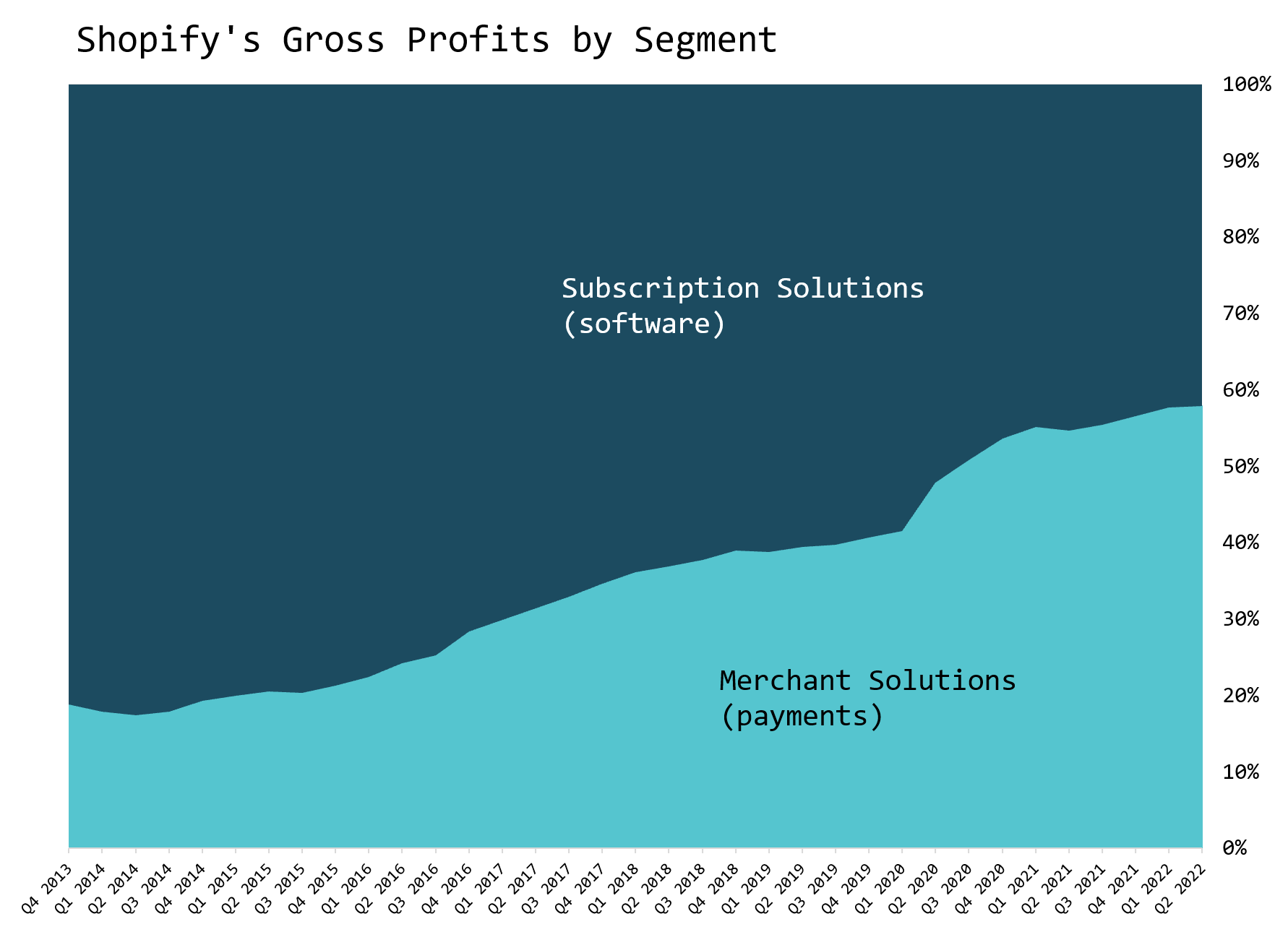

Over the years, payments have come to dominate not only Shopify’s take rate, but also its gross profits. The chart below, shown on a trailing twelve month basis, shows how software used to be 80 percent of Shopify’s gross profits. Now it has dropped to just 40 percent.

While software has a nearly 80 percent gross margin for Shopify, payments only carry a 42 percent gross margin. This growth in payments has dragged Shopify’s overall gross margins from over 60 percent to 52 percent.

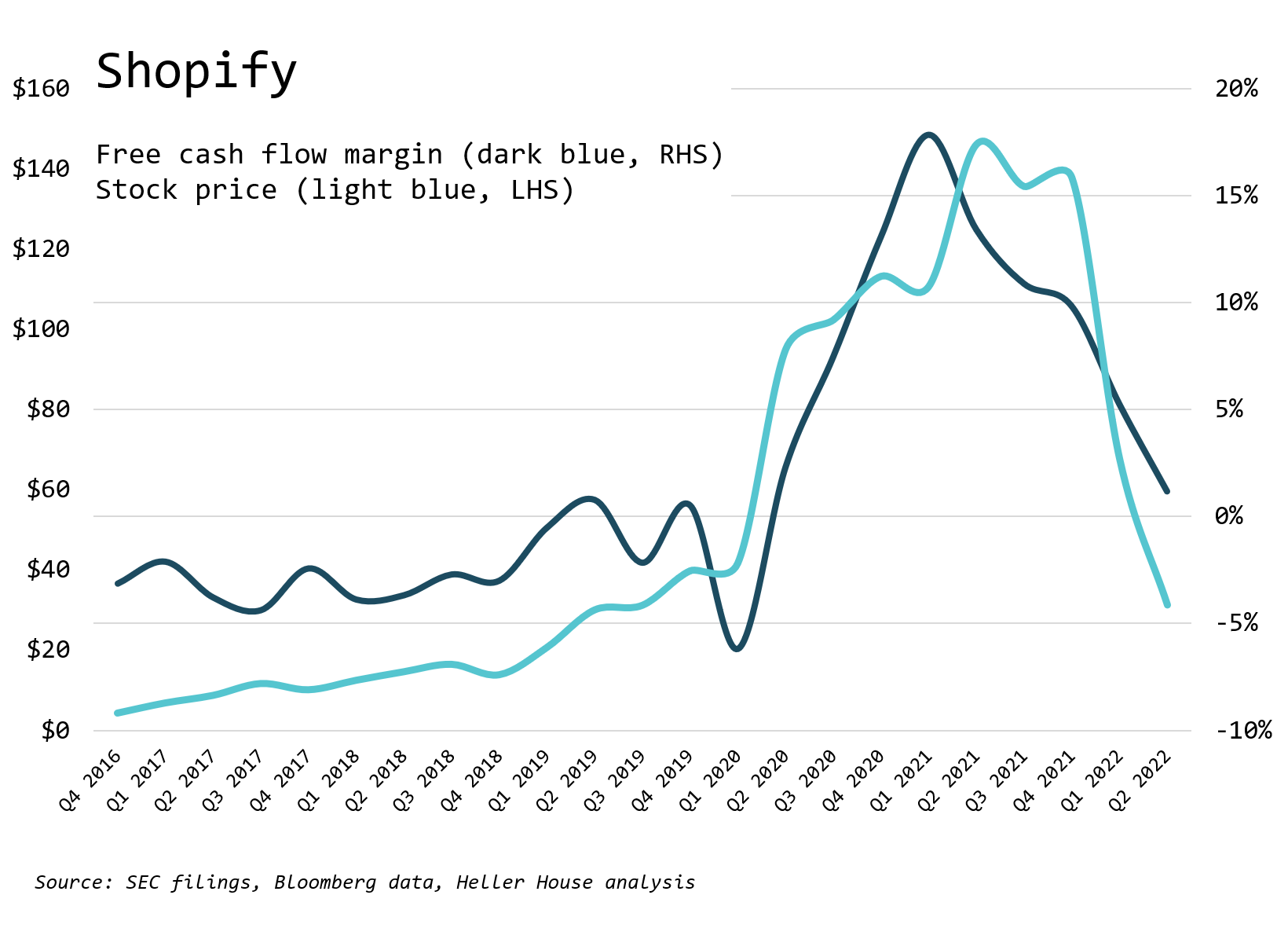

This shift has weighed on Shopify’s financials, yet the company has shown that it can make money. At the end of the Covid-fueled spike in demand—and a period in which the company contained its expense growth —Shopify was actually able to generate an 18 percent free cash flow margin on a trailing twelve month basis. That’s the peak in the dark blue line below, in Q1 2021:

While hard to disentangle Shopify’s subsequent stock price decline (light blue line) from the general malaise in high growth tech stocks, investors certainly aren’t happy to see the margin decline.

It was avoidable; Shopify had contained its expense growth, and if it had managed the company for profitability, margins might have been more resilient. Very likely, the stock price wouldn’t have declined 74 percent this year.

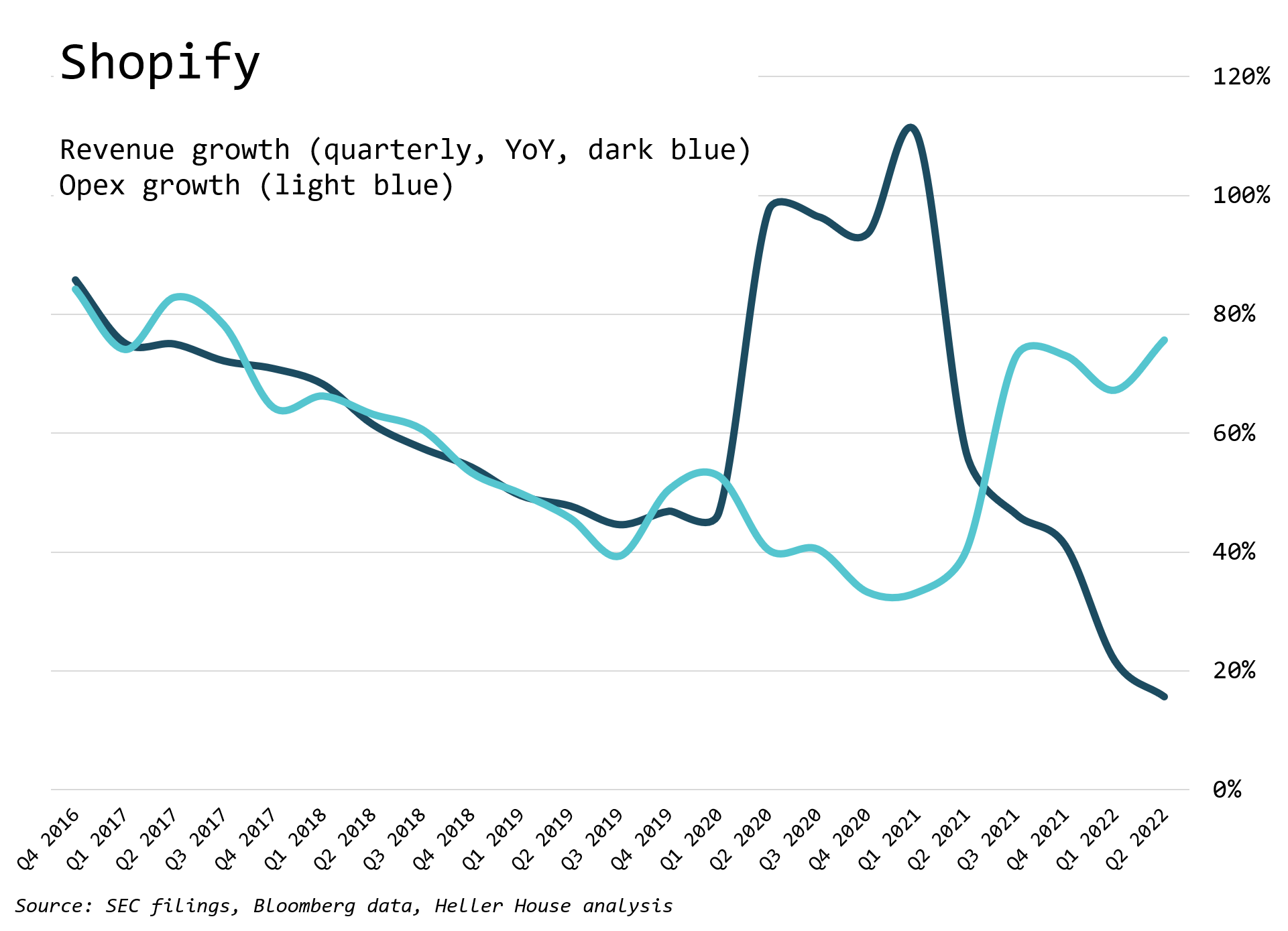

But the management team made the opposite bet: it thought the Covid spike in ecommerce would mean higher growth for longer. Operating expenses went from growing 40 percent year over year to nearly 80 percent in the most recent quarter. Meanwhile, revenue growth imploded to less than 20 percent:

This led to the collapse in Shopify’s profitability from the 18 percent peak free cash flow margin to just 1 percent in the last twelve months.

Valuation Challenges

There are therefore three critical challenges to valuing Shopify stock.

Can its growth rate recover to over 20 percent; how high can the take rate go; and what will be its eventual free cash flow margin?

Sell-side analysts seem to believe that top line won’t be a problem. Estimates are for $17.3 billion in revenue by the end of 2027, up from an estimated $5.5 billion this year. Analysts expect a 14 percent free cash flow margin by then, or $2.4 billion.

If we pencil that into a DCF model and assume that Shopify can keep its yearly share count dilution to only 1 percent per year, then the IRR from the current stock price of $36 is a mere 12 percent per year assuming a 30x exit multiple. At a 25x multiple, the IRR drops to 8 percent.

To get to $17.3 billion in revenue, though, Shopify’s GMV would have to grow to $630 billion assuming its take rate remains steady at nearly 2.7 percent. That’s more than 3x from the current level.

Shopify insiders recently bought some shares. Kaz Nejatian, VP of Merchant Services, followed suit, and posted the following on Twitter:

This morning, I liquidated some of my family's portfolio and bought a significant amount of $SHOP and for the first time ever talked to our team at Shopify about the stock price. pic.twitter.com/KzleJ7XzTH

— Kaz Nejatian (@CanadaKaz) May 11, 2022

Nejatian’s post is long on emotion but short on an actual investment thesis.

While it’s encouraging to see insider buying, it’s hard to tell if it’s signal or noise. Yes, Tobi Lutke owns a huge amount of Shopify stock, about $3.5 billion. Yet he’s sold hundreds of millions over the years, and his recent purchase, one day before Nejatian’s Tweet, amounts to only $13 million.

Wouldn’t it be interesting, though, if Shopify’s insiders gave investors some idea about what they think long-term take rates and profitability could look like?

Elon Musk, ever the iconoclast, did exactly this during Tesla's Q4 2014 earnings call. At the time, the company’s market cap was about $20 billion. Musk clearly laid out the investment thesis for Tesla stock:

Elon Musk Tesla Motors Inc. – Chairman & CEO

We are going to spend staggering amounts of money on CapEx, for good reasons and with a great ROI. It's important not to look at the CapEx in isolation because that CapEx is obviously being done for a reason in order to capture a substantial future revenue flow.

I am just saying the back-of-the-envelope—if you make certain assumptions, and I emphasize these are just certain assumptions, I am not saying they are true or that they will occur, but I'd bet that they do occur, personally, but just my personal opinion.

If you take this year's revenue, around $6 billion or thereabouts, and if we are able to maintain a 30% growth rate for 10 years, and achieve a 10% profitability number, and have a 20 P/E, our market cap would basically be the same as Apple's is today. That's going to require a bit of—on the order of $700 billion—obviously, getting that rolling requires some significant CapEx. But I am hopeful that we can do this without any significant dilution to the Company, maybe minor dilution but nothing serious.

When this call was held in February 2015, Apple's market cap was indeed "on the order of $700 billion." Later in the call, Musk was asked about how high operating margins could get, and he estimated around 10-15 percent, based on the company's 30 percent gross margins and how many percentage points would have to go into operating expenses.

Since that call, Tesla spent about $22 billion in capital expenditures, and Musk's estimates were spot-on. His thesis was perfectly articulated: “Our investments will allow us to grow at X rate, our profit margin will be Y, and our multiple will be Z”.

It was also incredibly accurate, if a tad conservative.

Tesla grew, of course, much faster than just 30 percent per year. Revenues swelled from $4 billion in 2015 (much less than Musk’s initial $6 billion estimate) to $67 billion in the trailing twelve months. The earnings multiple is much higher than 20x. The profit margin reached 14 percent in the last twelve months, the highest of any auto company. Tesla crossed the $700 billion market cap mark not in ten years, but in five.

Shopify, however, has given investors very little to hang their hats on. The payments take rate is expected to rise, but that’s it. What will profits margins ultimately be? Can the software take rate rise from its paltry 0.75 percent?

Importantly, will Shopify be able to scale up its own fulfillment quickly enough to counter the threat from Buy with Prime?

Shopify's 74 percent stock price decline damages internal morale, makes it harder to compensate employees, increases stock dilution, and sours investor sentiment.

Investing is challenging enough when there is a relatively clear line of sight to where a business might end up. By not providing investors with any long term view of its financials, Shopify is not doing anyone any favors.